Warning: This report contains details of physical and sexual abuse and discussion of suicide.

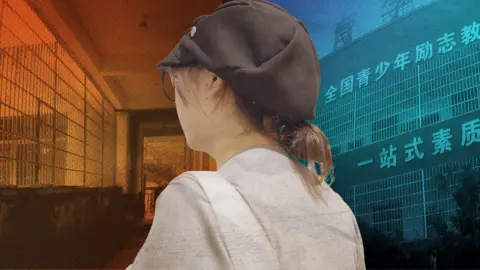

Baobao's heart still races when she smells soil after morning rain. It takes her back to military drills behind locked gates, with every day marked by fear at Lizheng Quality Education School.

For six months, at the age of 14, she hardly left the confines of the red and white building where instructors claimed to ‘fix’ young people deemed problematic by their families. Students endured severe punishments, with reports of relentless beatings leaving them unable to sit or lie down comfortably for days. Every single moment was agonising, recounts Baobao, now 19, speaking under anonymity.

A BBC Eye investigation brings to light multiple allegations of physical abuse, abduction, and sexual assault within the institution. Despite corporal punishment being banned in China for decades, testimonies from 23 former students reveal horrific treatment including forced exercises, beatings, and cases of rape.

The schools, operating under a booming industry that exploits anxious parents' desires for disciplined children, have seen numerous allegations of abuse surface publicly, yet many continue to function under new names or locations.

Undercover footage highlights how school staff mislead parents, impersonating authorities to forcibly transfer students. One former student was abducted during a family visit, driven away in a vehicle by individuals claiming to be law enforcement.

Baobao recalls her mother enrolling her when she began skipping school, only for her to realize that escape was impossible: They told me if I behaved well, I might be able to leave. The price for her six months there was substantial; her mother paid approximately 40,000 yuan ($5,700), and Baobao received no academic instruction.

Another former student, Enxu, experienced a similarly distressing fate: after being misled by fake police, she was beaten and sexually assaulted at a separate disciplinary school. Tales of abuse and manipulation are compounded by systemic failures in regulation and oversight of these institutions.

Despite public outcry and occasional shutdowns, the schools resiliently emerge anew. The covert profitability of this dreadfully unregulated sector poses grave ethical dilemmas about child welfare and parental desperation.

Both Baobao and Enxu express their horror at the circumstances that led their families to submit them to these schools, striking out against the practices that perpetuate harm over healing. As they strive for better futures, they advocate for the abolition of the very institutions that traumatized them, underscoring a critical need for societal and governmental reckoning with this clandestine industry.

Baobao's heart still races when she smells soil after morning rain. It takes her back to military drills behind locked gates, with every day marked by fear at Lizheng Quality Education School.

For six months, at the age of 14, she hardly left the confines of the red and white building where instructors claimed to ‘fix’ young people deemed problematic by their families. Students endured severe punishments, with reports of relentless beatings leaving them unable to sit or lie down comfortably for days. Every single moment was agonising, recounts Baobao, now 19, speaking under anonymity.

A BBC Eye investigation brings to light multiple allegations of physical abuse, abduction, and sexual assault within the institution. Despite corporal punishment being banned in China for decades, testimonies from 23 former students reveal horrific treatment including forced exercises, beatings, and cases of rape.

The schools, operating under a booming industry that exploits anxious parents' desires for disciplined children, have seen numerous allegations of abuse surface publicly, yet many continue to function under new names or locations.

Undercover footage highlights how school staff mislead parents, impersonating authorities to forcibly transfer students. One former student was abducted during a family visit, driven away in a vehicle by individuals claiming to be law enforcement.

Baobao recalls her mother enrolling her when she began skipping school, only for her to realize that escape was impossible: They told me if I behaved well, I might be able to leave. The price for her six months there was substantial; her mother paid approximately 40,000 yuan ($5,700), and Baobao received no academic instruction.

Another former student, Enxu, experienced a similarly distressing fate: after being misled by fake police, she was beaten and sexually assaulted at a separate disciplinary school. Tales of abuse and manipulation are compounded by systemic failures in regulation and oversight of these institutions.

Despite public outcry and occasional shutdowns, the schools resiliently emerge anew. The covert profitability of this dreadfully unregulated sector poses grave ethical dilemmas about child welfare and parental desperation.

Both Baobao and Enxu express their horror at the circumstances that led their families to submit them to these schools, striking out against the practices that perpetuate harm over healing. As they strive for better futures, they advocate for the abolition of the very institutions that traumatized them, underscoring a critical need for societal and governmental reckoning with this clandestine industry.